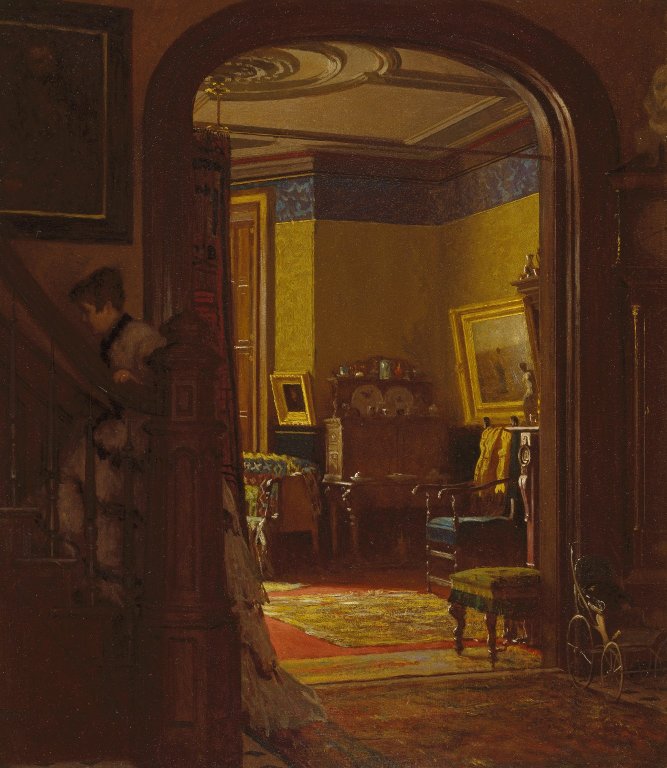

The Red Room, one of the diplomatic reception rooms on the first floor of the White House, during the Clinton administration.

In honor of inauguration week, I thought I’d post a few fun facts about the White House:

* “A house, for president” was authorized by Congress in March of 1792. Washington chose a Georgian townhouse as a model – not a palace – and that was significant. John and Abigail Adams were the first to live there, and Jefferson first opened the house for tours. It became known as the Exectuive Mansion.

* In 1814, the President’s house was burned by the British during the war, leaving only a shell, but James Madison rebuilt it rather than starting anew. The building became a phoenix rising up out the ashes.

* The distinctive curved south portico was added in 1824 and the grand entrance portico at the north was added in 1830.

* Andrew Jackson held a public reception in the mansion on inauguration day, and the event turned into a drunken mob scene. Jackson fled, and several thousand dollars’ worth of china was broken.

* By 1886, the White House was so badly in need of renovations, President Chester Arthur felt it would be less costly to build a new house. He tried to get $300,000 appropriated by Congress for that purpose, but the amount was refused, and the Army Corps of Engineers noted that the house could not be torn down, “its sentimental value is too great for Americans.”

* Theodore Roosevelt had McKim, Mead and White make interior changes in a classicist style, and added a West Wing with an oval office, separating the work and living spaces. Roosevelt officially changed the name of the building to the White House.

* In 1948 one leg of first lady Bess Truman’s piano fell through the ceiling and Congress finally appropriated money for renovation. The White House was gutted and rebuilt, with the first floor reserved for diplomatic functions, the second as living quarters, and the West Wing as offices. The two porticos were virtually the only architectural elements left intact.

* It has only been in the last generation that the interiors of the White House remain stylistically stable. Throughout the 19th century the White House went through short spasms of redecoration interspersed with long periods of rooms full of cast-off and worn-out furniture. Finally, beginning around 1960, Jackie Kennedy responded to the “federal” aesthetic imposed on the interiors by McKim and re-imposed by Truman renovations, and turned the White House into the American showplace it is today. She solicited donations of decorative arts, set up a curatorial and conservation programs, and established an endowment. Her work made the White House less like a working hotel that housed a family mandated to move every 4 or 8 years, and more like a museum.

More to come … the private lives of the presidents.